Peoples of this Land

Who has lived here and cared for this place?

THE INDIGENOUS ORIGINS OF TORONTO’S NAME

There are multiple theories about the Indigenous origins of our city’s name.

One widely accepted version is that the word Toronto comes from the Kanien’kéha/Mohawk Tkarón:to (tree in the water there). This word may refer to ancient fishing weirs at the narrows (now Atherley Narrows) between Lakes Simcoe and Couchiching, where ancestors of contemporary Indigenous Peoples gathered for thousands of years. They drove stakes into the water to block channels and create narrow openings to catch fish. The Wendat word for the same narrows would be Karonto (log lying in the water); they are known in Anishinaabemowin as Mnjikaning (fish fence). Here, Indigenous nations met in Council, fished, and traded as allies. The abundance of food the fish provided allowed for the hosting of large, extended gatherings. Archaeologists have dated stakes at the site to 2610 BCE, or roughly 4,500 years ago. Samuel de Champlain described these fishing weirs in use by the Wendat in his 1615 travel diary. Another possible origin for the name comes from the Wendat Tonrontonhk (land of plenty) but recent linguistic research may not support this.

The name Toronto appears to have migrated down the Carrying-Place Trail to its present location. French maps from the 1670s and 1680s label Lake Simcoe as “Lac de Taronto.” The portage route along the Humber River between Lakes Simcoe and Ontario became known as the “Passage de Taronto,” and the Humber as the “Rivière Taronto.” The French fur-trading fort established in 1720 on the Humber and later French forts on the waterfront became known as Fort Toronto. In 1793, John Graves Simcoe, the first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, named the settlement he founded York, but the Indigenous name was restored when the city was incorporated in 1834.

This area has long been a cultural crossroads. Many nations passed through while travelling east-west along the waterfront or north-south along the river and portage routes to the upper Great Lakes. We use the name Toronto, knowing that Indigenous Peoples have referred to the region by names in their own languages.

HISTORICAL INDIGENOUS PRESENCE IN THE GTA

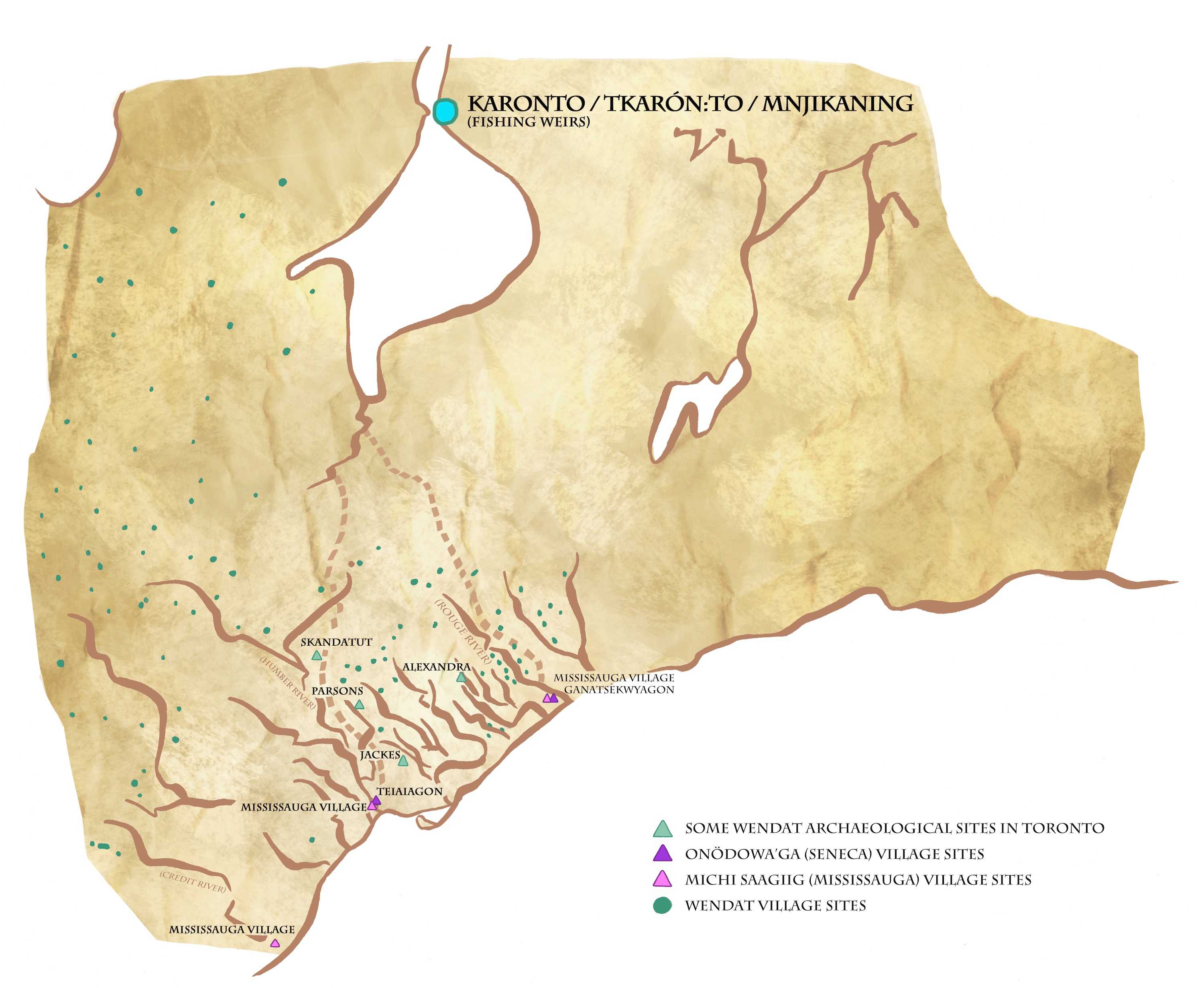

Some Ancestral Wendat sites

Parsons Site (Keele St. and Finch Ave.) mid-fifteenth century Village, ten Longhouses, subterranean Sweat Lodges, midden (refuse) areas, ossuaries. Trade items from long distances, stone and copper tools, ceramic pots, rolled tubular beads.

Alexandra Site (Highland Creek) first half of fifteenth century Two overlapping phases of occupation, possibly a union of two villages during times of duress. Twenty-nine semisubterranean Sweat Lodges.

Jackes Site (Avenue Rd. and Roselawn Ave.) late fourteenth or early to mid-fifteenth century village Pipes, pottery from multiple decorative traditions, and worked bone tools.

Skandatut Site (East Humber River, near Kleinburg), late sixteenth century Largest village along Humber, approximately two thousand people. Site is protected by Huron-Wendat Nation of Wendake, Quebec.

The archaeological record of the area indicates the presence of communities that would gradually become the distinct, sovereign entities we recognize today. The question of who was here first is not easy to answer: each group has a connection to the territory and origin stories to back it up.

Peoples around Lake Ontario/Ontarí:io or Skanadario (Great Lake or Beautiful Water):

c. 11,000 BCE. Nomadic hunters follow big game as glaciers retreat, making the region accessible to humans. Ancestors of contemporary Indigenous Peoples hunt, gather, and fish throughout the region for thousands of years. The flats along Toronto’s rivers host countless camps and fish-processing sites.

Even the lands under the waters of Lake Ontario hold artifacts and sites of occupation that were later covered up as melting glaciers and changing drainage patterns caused shorelines to shift.

800–1300 CE. Corn is brought to the area, and Longhouse cultures gradually develop, including that of the ancestral Wendat on the north shore of Lake Ontario and the Attawandaron/Neutrals just to the west.

At least some of the people who become the Wendat arrive in southern Ontario from the south around 1000 CE. The ancestors of the Anishinaabek are already living here. Anishinaabe Territory covers most of the region surrounding the Great Lakes. Some Anishinaabe stories detail migration to the Great Lakes from the salt waters to the east.

The Wendat and Anishinaabek become allies. The Wendat trade corn for furs and fish, the two groups intermarry, and some Anishinaabek overwinter in Wendat villages.

1300–c. 1610. Ancestral Wendat village sequences and burial ossuaries dot the Toronto landscape. Longhouse villages surrounded by immense cornfields are moved every fifteen to thirty-five years or so to gain access to fresh soils and timber. Artifacts reveal large trading networks with Anishinaabe allies and other Indigenous Peoples that extend as far as the Gulf of Mexico and Hudson Bay. A Council Fire is maintained at the fish weirs at the Narrows for centuries (and perhaps thousands of years) and is host to many meetings that confirm the alliance between the Wendat and Anishinaabek.

Mid-1400s. Widespread violent conflicts, possibly between Wendat communities or between the Wendat and Haudenosaunee or other neighbouring peoples, cause multiple small communities to merge into larger villages. Wendat villages expand, adding new Longhouses between older ones. Each of the Longhouse villages in the Toronto area hosts its own Village Council, which may have been part of a larger network of Nation Councils and a Grand Council in Wendake (after the formation of the Confederacy in the fifteenth century).

THE WENDAT AND THEIR NEIGHBOURS (C. 1600)

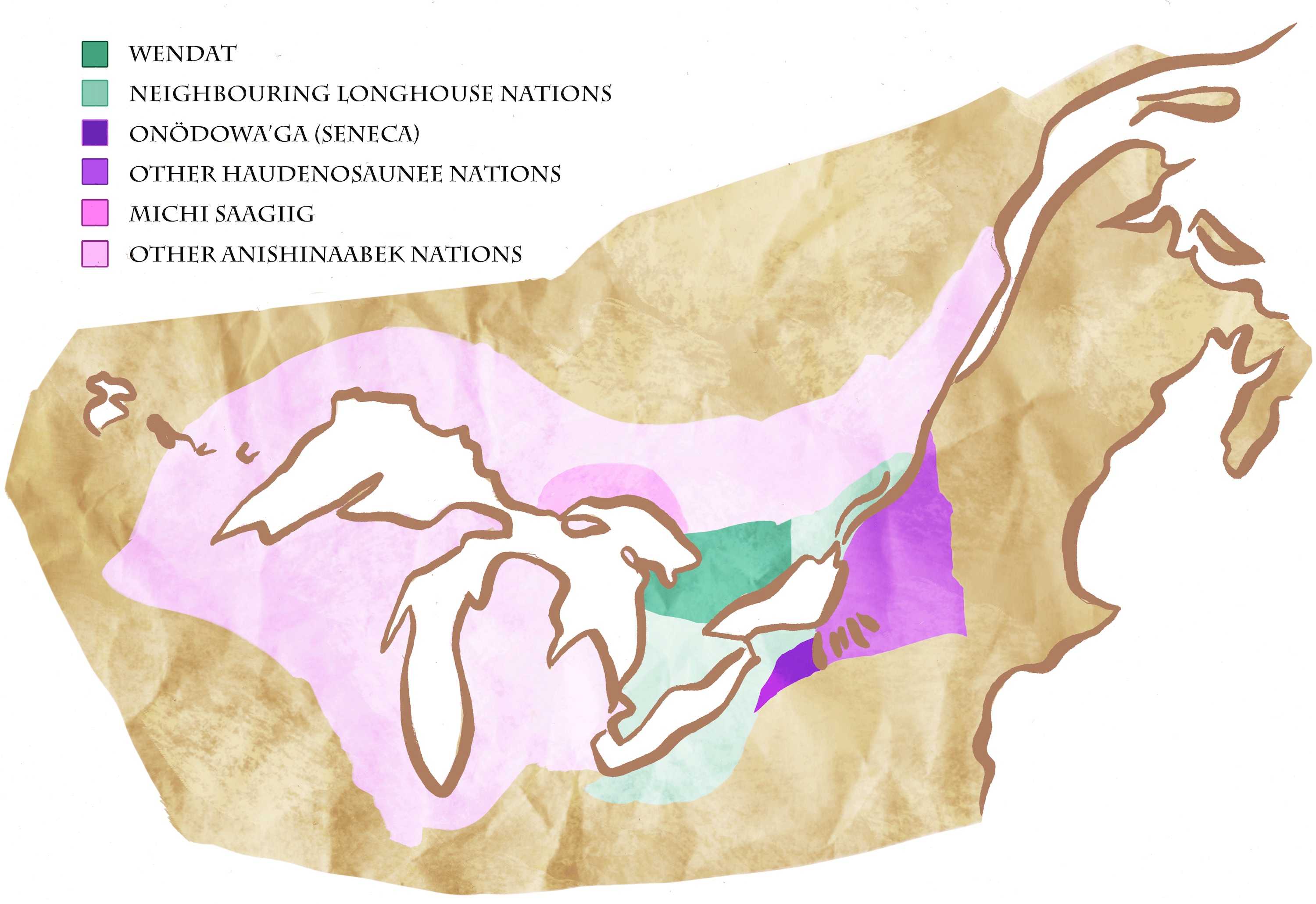

Rivers and lakes connected a network of Council Fires across the region. At each site, communities gathered to deliberate and assign responsibility for stewarding the lands, waters, and peoples in a specified territory. Some of these gathering places have been maintained to this day. The three main groups upholding this network of alliances and land-based memory are the Wendat Confederacy, the Anishinaabek, and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (including the Seneca).

TIMELINE OF THE WENDAT, SENECA, AND MISSISSAUGA IN TORONTO

Wendat, Seneca, and Mississauga are the names mentioned most frequently when speaking about Toronto’s Indigenous history.

1300–1600. Ancestral Wendat communities begin moving north and east of the Toronto area, possibly because they are seeking greater trade with Anishinaabe allies to the north, wish to avoid conflict with the Haudenosaunee, or are seeking new lands. By the early 1600s, the last Wendat group in the Toronto area, the Tahonhtayenrat/People of the Deer, has moved north from Skandatut to join the Wendat Confederacy between Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay. Known as Wendake, this region is favourably located on agricultural lands along canoe routes leading to the upper Great Lakes. The lands at Toronto recuperate, village sites grow over, but the area is maintained as Wendat hunting territory.

1648–50. The Seneca and Mohawk of the Haudenosaunee (Five Nations) Confederacy push north from their homelands near the Finger Lakes region south of Lake Ontario, attacking the Wendat Confederacy and the Attawandaron/Neutrals and forcing them and the Anishinaabek around Georgian Bay to move farther north, west, and east.

1660s–c. 1687. The Seneca establish two villages in the GTA, part of a network of seven Haudenosaunee villages along the north shore of Lake Ontario and on the Grand River:

-

Humber River/Teiaiagon (Crosses the Stream?). Situated on a height of land overlooking the east bank of the Humber River. Although the village has never been fully excavated, many graves have been found on the site. It may have been occupied by different peoples over the centuries.

- Rouge River/Ganatsekwyagon (Among the Birches). Likely at the site of present-day Bead Hill, where many trade beads have been found. The first documented Europeans in the GTA are French Sulpician missionaries, who spend a winter at Ganatsekwyagon in 1669–70, though explorer Étienne Brûlé may have reached Lake Ontario via the Humber in 1615.

1660s–1690s. The Anishinaabe Three Fires Confederacy – the Ojibwe, Odaawaa, and Potawatomi – push south to attack the Haudenosaunee, reclaiming their own territories and those of their Wendat allies. The Mississauga, originally from the north shore of Lake Huron, move to the north shore of Lake Ontario. The Seneca retreat to their homelands south of Lake Ontario.

c. 1695. One group of Mississauga establishes seasonal villages on the Credit River, on the Humber River across from the former site of Teiaiagon, and at Bead Hill, as well as camps on other local waterways. They become known as the Mississaugas of the Credit.

ACTIVITIES

Indigenous peoples have been referred to by many different names, spelled many different ways, by Europeans. Their territories were often inaccurately represented on early maps, which were drawn to further colonial aspirations. Countless errors, misinterpretations, and revisions confuse the land-based knowledge held in the Indigenous names for places and for themselves. Translation of Indigenous words to English may lose much of their deeper meaning.

Not all the peoples listed in the activities below would have lived within Toronto’s current boundaries, but their network of Council Fires would have brought them into relationship with the rivers, territories, and peoples here. This list isn’t definitive, as groups have taken on different forms and identities over the centuries.

We, like many others, use the word nation as a shorthand for various Indigenous political entities, but these entities often bore little resemblance to the European idea of nation-states where ruling elites wielded power and authority over the rest of the population and the territory.