Peace Between Nations

The Beaver Wars

Throughout the 17th century, competition in the fur trade aggravates pre-existing Indigenous rivalries and upsets the regional balance of power, resulting in over a century of warfare, political destabilization and territorial movements involving the Wendat, Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek confederacies as well as their French and British colonial allies.

THE MISSISSAUGA DISPLACE THE SENECA IN SOUTHERN ONTARIO

Teiaiagon and Ganatsekwyagon are two Seneca outposts established in the 1660s at what will become Toronto. By 1687 they are vulnerable because of ongoing wars that rage between the Haudenosaunee and the French (and their Anishinaabe allies) through most of the seventeenth century.

The French, supported by the Anishinaabek, undertake military campaigns against the Mohawk and Seneca in their homelands south of Lake Ontario, destroying many villages and crops. At the same time, the Three Fires Confederacy begins a military campaign to regain Anishinaabe territories and those of their Wendat allies in south central Ontario. A further aim is to gain control of transportation routes from the upper Great Lakes to Lake Ontario to ensure access to both English and French fur traders.

Sometime after 1687, the Seneca abandon their villages on the Rouge and Humber and move south of Lake Ontario to rejoin the main body of Haudenosaunee, although they continue to hunt on the north shore. There are many interpretations of the Seneca’s departure. Some stress defeat by the Anishinaabek, others the French military campaign, and still others diplomatic agreements between the Anishinaabek and Haudenosaunee.

A group of Anishinaabek from near the Mississagi River on the north shore of Georgian Bay relocates to the north shore of Lake Ontario and becomes known as the Michi Saagiig/Mississauga. Some of this group fight the Haudenosaunee in battles to the east and establish themselves in the Peterborough area. Others travel down the Humber and move into the Toronto area, establishing themselves on the Rouge, Humber, Credit, and other rivers. Anishinaabe Oral Tradition records a decisive battle at or near Burlington Bay in the 1690s.

The Anishinaabek consolidate their control over southern Ontario through the relighting of old Council Fires and the establishment of new ones, such as the one at the mouth of the Credit River. According to a Mississauga Oral Tradition, because they are “people of good credit” in their dealings with fur traders, they become known as Mississaugas of the Credit, and the river acquires its European name.

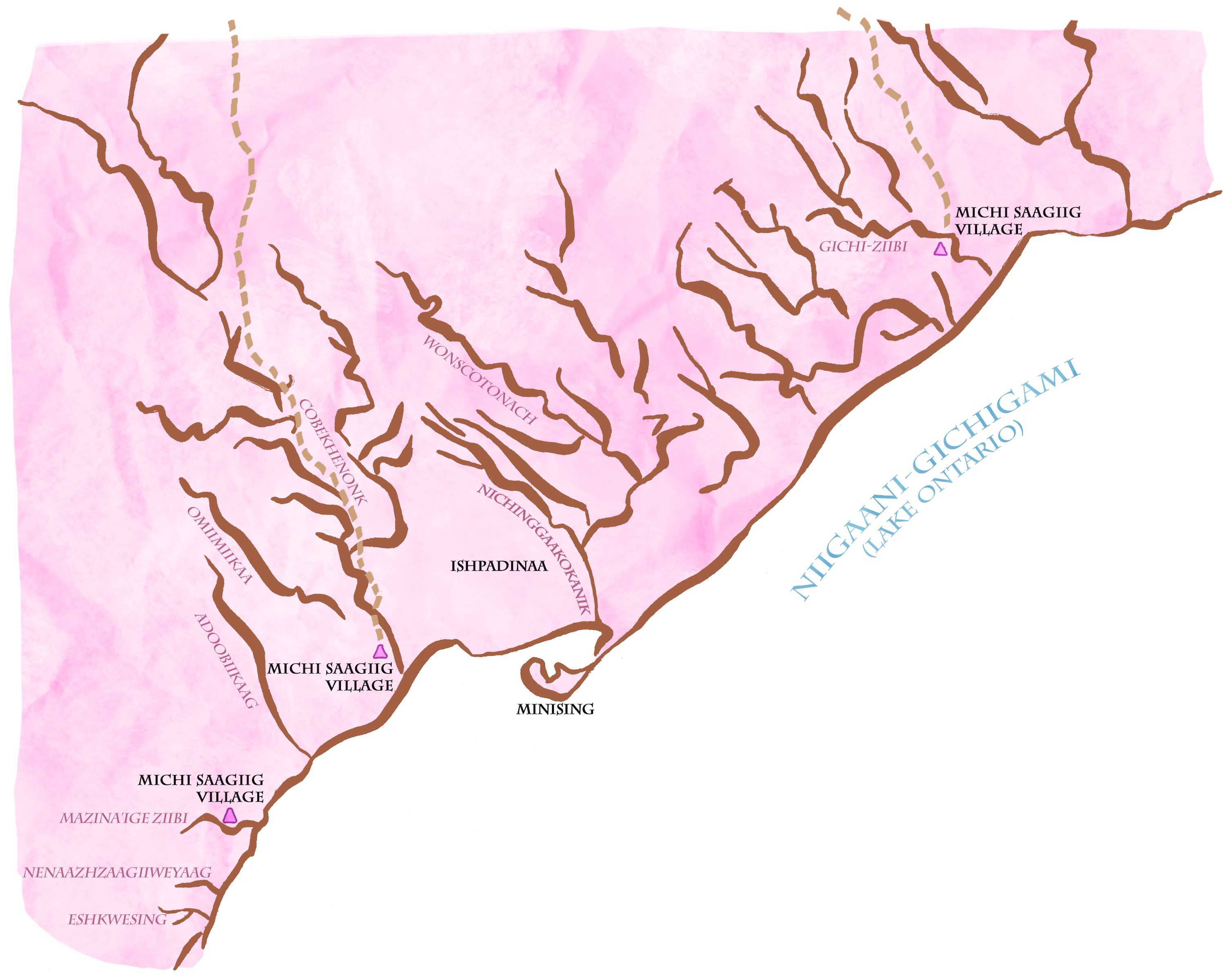

MISSISSAUGA IN THE GTA (C. 1700)

MISSISSAUGA PLACE NAMES IN THE TORONTO AREA

The Mississauga establish fishing camps and, in some cases, seasonal villages at the outlets of the rivers in the Toronto area and along the western end of Lake Ontario, renaming and restorying the physical landscape as they do so.

Nenaazhzaagiiweyaag (Sixteen Mile Creek) Variations: Auzahzahkewayyogk

Eshkwesing (Twelve Mile Creek/Bronte Creek) Variations: Ashquasink

Mazina’ige - ziibi (Credit River)

Variations: Mahzenahekasepeh, Missinnihe Translations: To write, or to give or make credit. It is said that French fur traders sent trade goods upriver in the fall, and the Mississauga and other Anishinaabek sent payment in furs downriver in the spring.

Adoobiikaag (Etobicoke Creek) Variations: Adoopekog Translation: Plentiful alders/place of alders. There

was a Mississauga fishery on the flats, a factor in the Mississauga’s future attempts to secure the shores of the rivers for their exclusive use.

Omiimiikaa (Mimico)Translation: Place of the wild pigeons. Now extinct, passenger pigeons may have feasted on the abundant acorns from the nearby black oak savannas, which extended beyond present-day High Park.

Cobekhenonk (Humber River) Variations: Cobechenonk, Gabeshinong, Gabekanaang-ziibi. Translations: Leave their canoes and go back; place of rest and refreshment; overnight camping stop. The Mississauga establish a small village on the west side of the Humber, across from the previous Seneca village of Teiaiagon.

Ishpadinaa (Spadina) Translations: High hill; high place. From atop the height of land (ancient shoreline) near present-day Casa Loma, the Anishinaabek can view activity on the waterfront, including trade with the French.

Wonscotonach (Don River)

Translations: Perhaps back burned ground, burning bright

point, likely referring to the practice of cultural burns to maintain the pine savannas in this area or fishing with torches at night. The Don River area is referred to as Nichinggaakokanik (A good place for pines).

Minising (Toronto Islands) Variation: Minnesink

Translation: Island. A narrow sandbar near the Don River led to a peninsula, which was later severed by a storm to become the Toronto Islands.

Gichi-ziibi (Rouge River)

Translation: Big river. Eastern limit of Mississaugas of the

Anishinaabek – Haudenosaunee Peace, 1700

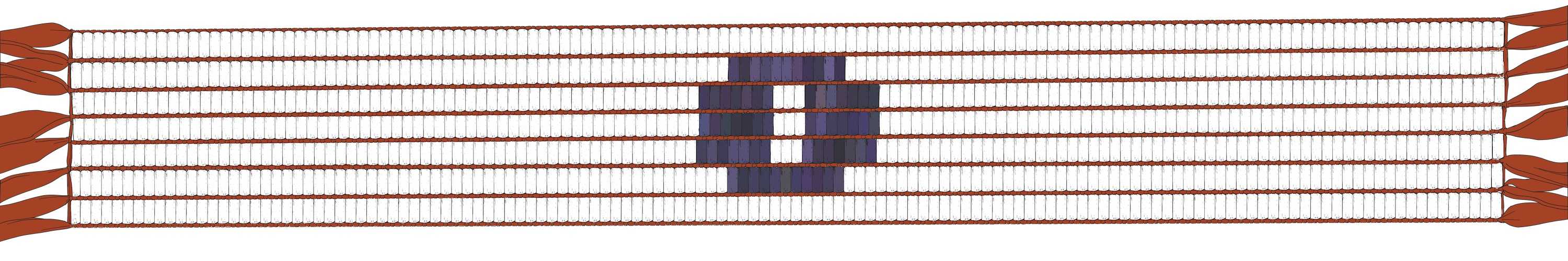

WHITE WAMPUM

Denoting peace; good relations.

By the late 1690s, both the Anishinaabek and Haudenosaunee want to end their war with each other, which has been inflamed and prolonged by ongoing imperial competition between the French and British (their respective colonial treaty partners). The peace agreement made between the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek in 1700 provides the foundation for an enduring entente between these previously bitterly warring nations that has now lasted more than three hundred years. However, the terms of the peace, as exemplified by the Dish with One Spoon Wampum, remain contentious, and the Wampum has come to be interpreted in many different ways.

The Dish with One Spoon is frequently mentioned in Toronto land acknowledgements but there is no consensus among local First Nations as to its meaning and considerable concern about its misapplication. Anishinaabek and Haudenosaunee agree that it was intended as a broad peace agreement covering much of the Great Lakes region, but the assertion that it is an agreement to “peaceably share” territory or jurisdiction on the north shore of Lake Ontario is a contested interpretation, rejected by the Mississauga for its blurring of territorial boundaries. Rather than the Dish extending a general and perpetual co-sovereignty over these territories, they argue that access to hunting, fishing, and gathering grounds was granted to the Haudenosaunee through intertribal diplomacy and subject to express permission.

The Dish with One Spoon . . . is probably one of the most misunderstood wampums. When the Haudenosaunee asked us if they could come here and hunt, we said, “Well, yeah, you can come up here and hunt, and when you come up and do the friendship circle or smoke the pipe, you are allowed to hunt during that period of time, but not forever.” The way they interpret it today is that this is also their hunting ground, which is not the way it is.

– Michi Saagig Elder Doug Williams

The Dish with One Spoon is also widely cited (and admired) today for its stewardship ethic and the reciprocal responsibilities with all of creation that it foregrounds, a reading that draws on the more general metaphor of the land as a dish to be shared and cared for to ensure ongoing sustenance and life. However, Anishinaabe leaders have expressed concern that such an interpretation can lead to the misconception that the Dish with One Spoon agreement opens up this territory to all nations, again undermining Indigenous Territorial Rights and sovereignty.

Lastly, as a treaty between Indigenous partners, its relation to today’s non-Indigenous population in Toronto is unclear.

I think we did invite them [settlers] to come and take from the dish but with the understanding that there are these laws: that you only take what you need, you always leave something in the dish for other people, and you keep the dish clean. So you could say our treaty relationship is trying to mentor what we call our younger brother, our treaty partner, into how to live here within this great dish. There wasn’t a formal occasion where we extended that to them, but I think the reality is that we needed them to live well within the dish so they wouldn’t pollute it, wouldn’t destroy all the animals, or cut down all the trees.

– Tuscarora historian Rick Hill

THE ETERNAL COUNCIL FIRES BELT

Another related Wampum agreement that sheds light on the terms of peace between the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabek is the Eternal Council Fires Belt, also referred to as the Yellowhead Belt, after its mid-nineteenth-century Anishinaabe Wampum Keeper Chief Yellowhead, of Mnjikaning/Rama. It was originally given to the Anishinaabek by the Haudenosaunee, likely in the 1690s. The actual belt is missing and may have been destroyed in a fire, but a detailed reading of it from an important Anishinaabe – Haudenosaunee Council in 1840 details the Council Fires to be maintained by the Anishinaabek and recognized by the Haudenosaunee to keep the path of peace between their territories clear. The Credit River is one of these Council Fire locations. There is also one at the Narrows of Lake Simcoe (Mnjikaning, Taranto, Tkaronto), where Toronto likely got its name.

REKINDLING A COUNCIL FIRE

Renewing and reinvigorating an alliance.

In 1840, fifteen Haudenosaunee Chiefs from Six Nations travel to a General Council on the Credit River at the Mississauga Council Fire, where they meet with twenty-two Anishinaabe Chiefs and warriors. The Anishinaabek and Haudenosaunee are facing many common issues and decide to renew their alliance to preserve their sovereignty and land in the face of intensifying British colonial encroachment.

The delegates appoint a “chairman,” following the ways of the settlers, and Mississaugas of the Credit Chief, Peter Jones, formally records the proceedings as “secretary.” Yet despite these changes, the treaty partners follow Traditional Protocol for renewing agreements. Each treaty party takes a turn reciting their understanding of their relationship and their interpretations of what is represented in the belt, rather like the process of confirming the minutes of a previous meeting at the start of a modern business meeting.

The chairman, Mississauga Chief Joseph Sawyer, opens the Council:

That the Great Spirit has brought us together in health and peace. That as they, the Mohawk chiefs, had expressed a wish to meet their Chippeway [Anishinaabe] brethren, he had sent for them in order to smoke the pipe of peace together, and thus renew the treaty of friendship which had been made by our forefathers. That the time was when the hearts of our forefathers were black towards each other, and much blood was shed.

The Good Spirit inclined the hearts of our forefathers to kindle the great council fires, when the pipe of peace was smoked, the tomahawk buried, and they took each other by the arms, and called each other BROTHERS. Thus their hearts, formerly black, became white towards each other.

He had sent for them that the council fire, kindled by our forefathers, might be rekindled by gathering the band together, as the fire was almost extinguished. He hoped, when it was lighted, the smoke would ever ascend in a straight line to the Great Spirit, so that when the eyes of all our people looked upon it they might remember the treaty of our forefathers.

In this belt, the Haudenosaunee recognize and acknowledge the location of Anishinaabe Council Fires and the Clan responsible for each one, thus recognizing Anishinaabe Clan governance in these areas. The Credit River and the Mnjikaning Narrows are named as key locations for the upkeep of the Dish. In contrast to the reading by Buck, Yellowhead specifies that Haudenosaunee access to the Dish at the Narrows has been forfeited by overfishing by the Mohawks of Kahnawà:ke and that Haudenosaunee hunting on the north is conditional on peace and their coming to Council.

John S. Johnson, one of the Mohawk Chiefs, addresses the council and provides a Haudenosaunee reading of the same Wampum Belt. This process of reflection and adding more information is part of the General Council process of witnessing, restating, and confirming understandings of the imagery on the belts.

[Johnson] then explained the emblems contained in the wampum belt brought by Yellowhead, which, he said, they acknowledged to be the acts of their fathers. Firstly, the council fire at the Sault St. Marie has no emblem, because then the council was held. Secondly, the council fire at Manitoulin has the emblem of a beautiful white fish; this signifies purity, or a clean white heart – that all our hearts ought to be white towards each other. Thirdly, the emblem of a beaver, placed at an island on Penetanguishene Bay, denotes wisdom – that all the acts of our fathers were done in wisdom. Fourthly, the emblem of a white deer placed at Lake Simcoe, signified superiority; the dish and ladles at the same place indicated abundance of game & food. Fifthly, the eagle perched on a Fall pine tree at the Credit denotes watching, and swiftness in conveying messages. The eagle was to watch all the council fires between the Six Nations and the Ojebways; and being far-sighted, he might, in the event of anything happening, communicate the tidings to the distant tribes.

Sixthly, the sun was hung up in the centre of the belt, to show that their acts were done in the face of the sun, by whom they swore that THE OJEBWAYS AND THE SIX NATIONS they would forever after observe the treaties made between the two parties . . .

Mr. Johnson also informs the Ojebways that they would, at some future day, desire to hold another council with all the Ojebways and Ottawas, and that they would let the eagle know that he may take the message to the white deer, who would decide when the council should be held.

At the Council’s conclusion, Yellowhead presents the Six Nations with two strings of White Wampum, as a memorial or pledge of what has been transacted between the two parties. The Chiefs of the Six Nations return the Wampum Belt to Yellowhead, and both groups leave, “shaking each other by the arm; which method was adopted by our forefathers when the treaty of friendship was first formed.” Peter Jones, as secretary, prepares the written record of the meeting and writes: “Thus ended the renewal of the treaty, with which all present were much pleased.” But he appears to minimize the differences in interpretation of Haudenosaunee hunting and fishing rights evident in the Wampum readings by John Buck and Johnson, on the one hand, and Yellowhead, on the other.