The 1764 Treaty of Niagara

Carrots & Sticks

Sir William Johnson, former British agent to the Haudenosaunee and now superintendent of Indian affairs for the northern colonies, is one of the richest and most powerful men in British North America: a fur trader, rum dealer, slaveholder, and extensive landowner. His task is to establish and maintain peaceful relations with Indigenous nations while also advancing Britain’s interests. He has a singular understanding of Indigenous Diplomatic Protocol through his close relations with the Mohawk, including through his partner, Molly Brant, an influential Mohawk Clan Mother. Adopted into the nation and made an Honorary Sachem, Johnson is the main British intermediary with the Haudenosaunee Confederacy.

It is Johnson who recommends extending the Haudenosaunee-British Covenant Chain to members of the Western Alliance to restore peace and gain control of territory formerly claimed by France. Although an architect of the Royal Proclamation’s provisions for Indigenous Peoples, he understands that the Proclamation must be ratified through Indigenous Diplomatic Protocol to be accepted. To accomplish this, he plans a diplomatic show of force: a grand Treaty Council at Fort Niagara, now a frontier of British-controlled territory.

He writes to General Thomas Gage, Amherst’s replacement as commander-in-chief of British forces in North America:

At this treaty... we should tie them down (in the Peace) according to their own forms of which they take the most notice, for example, by exchanging a very large [Wampum] belt with some remarkable & intelligible figures thereon expressive of the occasion which should always be shown to remind them of their promises.

To bring all nations to the proposed Treaty Council, Johnson uses both carrots and sticks: he threatens war for those who don’t attend and promises to restore trade to those who do. He recognizes that Indigenous sovereignty and independence must be respected (for now) though he anticipates that Indigenous nations will disappear over time and British hegemony (and settlement) will be assured.

Sir William Johnson outlines his strategy to Cadwallader Colden, governor of New York colony:

With regard to trade I think nothing can have a better effect on the Indians than the prohibition of it for some time, which will make their wants the greater, & consequently point out to them ye inconveniency & loss they sustain by a War with us, which they have not as yet sufficiently felt, at the same time it will be expected by all the Nations who make Peace that trade be opened as usual.

He elaborates further to General Gage:

Whenever it may happen that a peace is agreed upon, I apprehend it will be Expedient to treat with each Nation separately... This way of proceeding I have always observed in my transactions with them, particularly at Detroit in 1761, when I did all in my power in private conferences to create a misunderstanding between the 6 Nations, & Western Indians, as also between the latter & those of Ohio so as to render them jealous of each other, and the same has had some effect on several of them; I have since pursued the like steps in all my proceedings, for could they arrive at a perfect union, they must prove very dangerous neighbours.

We will see this tactic of fomenting division play out again and again in British dealings with Indigenous nations, as we did with the French. The British engage in Treaty Councils as grand acts of political theatre and position themselves at the apex of a vast system of alliances, from where they can adjudicate conflicts they helped to sow.

WHITE BIRD

An official spokesperson, a direct line of communication. In Anishinaabe culture, birds are messengers. A white bird symbolizes purity and honesty.

In late 1763, Johnson sends out messengers from the Algonquin and Nipissing Nations with paper copies of the Royal Proclamation and strings of Wampum. They cover territory that stretches from Nova Scotia to Hudson Bay to the Gulf of Mexico and the Mississippi River and invite Indigenous nations to a Council at Niagara the next summer. Fur trader Alexander Henry the Elder records the speech of one of the messengers.

My friends and brothers, I am come, with this belt, from our great father, Sir William Johnson. He desired me to come to you, as his ambassador, and tell you, that he is making a great feast at Fort Niagara; that his kettles are all ready, and his fires lit. He invites you to partake of the feast, in common with your friends, the Six Nations, which have all made peace with the English. He advises you to seize this opportunity of doing the same, as you cannot otherwise fail of being destroyed; for the English are on their march, with a great army, which will be joined by different nations of Indians. In a word, before the fall of the leaf, they will be at Michilimackinac, and the Six Nations with them.

CANOE

Indigenous nation, jurisdiction, society

After receiving their invitation, the Saulteaux Anishinaabek from the Sault Ste. Marie area consult with Mikinaak, the Great Turtle, through a Jiisakiiwin (Shaking Tent Ceremony) to learn if it is safe to attend the Council at Niagara. The Spirit crosses Lake Huron to Niagara then on to Montreal.

At Fort Niagara, he had seen no great number of soldiers; but, on descending the Saint Lawrence, as low as Montreal, he had found the rivers covered with boats, and the boats filled with soldiers, in numbers like the leaves of the trees. He had met them on their way up the river, coming to make war upon the Indians.

The spirit assures them they will be received as friends at Niagara:

Sir William J will fill their canoes with presents; with blankets, kettles, guns, gun powder and shot, and large barrels of rum, such as the stoutest of the Indians will not be able to lift; and every man will return in safety to his family.

AT THE COUNCIL

Two thousand Indigenous delegates from twenty-four nations across the Great Lakes and beyond gather at Niagara in the summer of 1764 to broker peace with the British. Haudenosaunee leaders are present, but they are already linked to the British through the near century- old Covenant Chain. Hard-nosed negotiations proceed throughout July. They lead to prisoner exchanges and a cession of land at Niagara by the Geneseo Seneca that secures British access to the “upper country” and its furs.

Johnson gives assurances that the British will respect Indigenous sovereignty and territory. No settlements will be made without permission. Settlers who commit crimes against Indigenous People will be prosecuted. Treaty partners will enjoy the Crown’s protection, and – crucially – trade will resume, but only if the British receive satisfaction for the harm done to them during the recent war.

But as for those nations who have obstinately maintained the war & thereby justly merited our highest resentment, they must expect nothing but punishment & to which end an army is now assembled at this place & will proceed agt them supported by a large number of those Indians most zealous in defending the subjects of Great Britain & in punishing the guilty [i.e., the Haudenosaunee Confederacy].

PRESENTS, NECESSARIES OF LIFE

Trade goods (guns, power, cloth, kettles, etc.) given at Treaty Councils and renewals. A pledge from the Crown ensuring that Indigenous treaty partners will have the means to support themselves and flourish as nations.

Johnson’s military threats are perhaps not entirely credible, given Britain’s lack of success in ending Pontiac’s War through military means, but Britain now has a monopoly on the fur trade. All nations who do not join this Pax Britannia will be cut out of the evolving economy and suffer greatly.

The Odaawaa, like many former allies to the French, come to Niagara in great want of trade.

Our families are in much distress. We beg you will permit us to trade as we have some furs and that the Trade may be reasonable. We hope the Traders will take a Buckskin as a Beaver and two doeskins as of the same value. Also, four raccoons for a beaver and one bearskin, two small beavers to be as one and that you will take our deerskins. A Belt of 8 rows.

SMOKING A PIPE

Tobacco carries words and intentions to the Creator, bearing witness to an agreement and its spiritual intent.

Seven boatloads of presents and at least eighty-four Wampum Belts are exchanged during the month-long Treaty Council, which is conducted as a series of mini Councils with the various nations, tailored to their specific circumstances. Johnson tries to make separate agreements, but a united front foils his efforts, as Chiefs from different nations regularly confer with one another.

Chief Wabbicommicot receives a significant Wampum Belt from Sir William Johnson because of his influence over the Anishinaabek, his pledge of loyalty to the British in 1761, and his role in promoting peace. Johnson asks Wabbicommicot and the Mississauga to return to their home near Toronto to guard access to Fort Niagara and Carrying Place so that trade may resume in the region.

Dr. Melanie J. Newton

Caribbean Rum

Dr. Melanie J. Newton

What is Triangular Trade?

CHAIN or BELT

The political relationship created through treaty.

On August 1, 1764, a grand peace and alliance are concluded. The Covenant Chain, which had united the British and Haudenosaunee for many decades (gradually incorporating other nations), is extended to the Western Alliance, including the Anishinaabek and the Wyandot. Through this process, the principles articulated in the Royal Proclamation are transformed and accepted by the Indigenous nations present, not as a top-down edict but as a treaty.

As a symbol of this new relationship, Johnson presents the 24 Nations and the 1764 Great Covenant Chain Wampum Belts to the assembled nations. The belts are to be kept by the Odaawaa of Michilimackinac, on behalf of the Western Alliance.

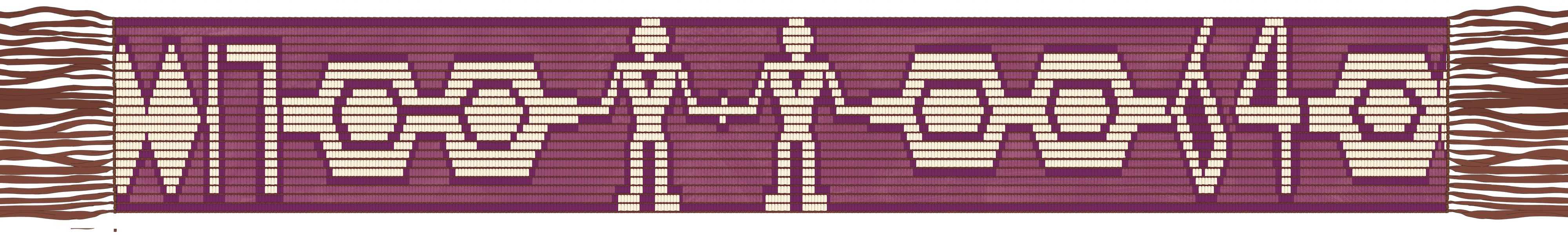

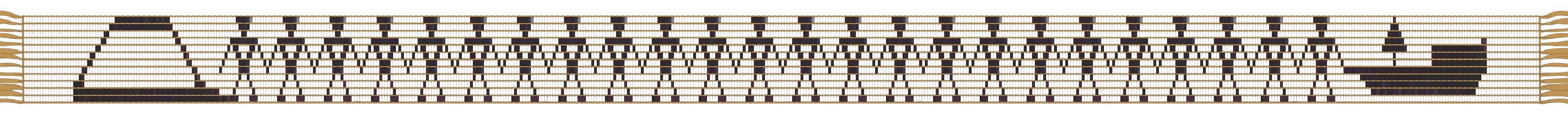

The 1764 Great Covenant Chain Wampum Belt

Two men, hearts visible, hold hands in the centre of the belt. The hexagons on either side of them include images that represent the links of a chain or the “strong hills” or British forts where Council Fires will be maintained so Chiefs can meet, negotiate with colonial officials, and receive presents. This imagery represents the promise to return to talk.

Diamond shapes at the edge of the belt may represent Indigenous Council Fires of the nations to the west and east. At the left end of the belt, the diamond is incomplete, perhaps suggesting the existence of prior treaties. At the right end, an unfinished diamond may suggest that the treaty relationship will continue. When the two ends of the belt are joined to form a circle, the incomplete diamonds form two diamonds, representing two Council Fires or nations – the British and Western Confederacy – united by treaty.

The 24 Nations Wampum Belt

This Wampum represents Britain’s promise to ensure the sustenance of life (symbolized through the delivery of presents) to the Haudenosaunee and Western Confederacies forever. At the right end, a ship – representing the British – is loaded with goods for the twenty-four nations, who are bound together by the cord of friendship secured to the boat. The mountain or rock at the left end of the belt represents North America, Indigenous Territory. The belt conveys that the British presence on Indigenous Territory is subject to Indigenous Peoples’ permission and must be accompanied by a pledge for mutual benefit.

A Founding Constitutional Moment

The Treaty of Niagara is a founding constitutional moment, a meeting of distinct legal orders – British and Indigenous – not an imposition of colonial law. It creates a new alliance for mutual benefit (some have referred to it as Canada’s first Confederation). The British are not granted legal sovereignty or jurisdiction over new lands (though they will claim them). Instead, they are permitted to settle on Indigenous Territories under explicit conditions: by making treaty – and by keeping their treaty promises.

PULL ON A CHAIN, A ROPE, A BOAT, A VESSEL

To ask for assistance, to invoke the treaty responsibilities of your partner.

Eighty-eight years after the Treaty of Niagara, Johnson’s words are recalled by Jean-Baptiste Assiginack (“Blackbird”), a War Chief of the Odaawaa, keepers of the Covenant Chain Wampum Belts. A gifted orator, he shares the responsibility of remembering the talk associated with the Great Covenant Chain and 24 Nations Wampum and participates in numerous Councils where the promises associated with the belts are remembered. At these councils, hundreds, sometimes thousands, of members of the Western Alliance gather to renew the Covenant Chain – and receive gifts from the Crown symbolizing its ongoing commitment to fulfill its responsibilities. In 1862, Assiginack recalls Johnson’s promise at Niagara as the Crown’s guarantee that Indigenous nations will have the capacity to sustain their lives and flourish as nations.

Speak the following text, a reading of the Niagara Belt by Jean-Baptiste Assiginack in 1851, aloud. Find a short phrase to work with. Select syllables to elongate or emphasize parts of the phrase. Let the promises take up a lot of space. Enjoy the alliteration. Find a memorable way to repeat your text selection: swap words or word order if needed. Repeat it aloud while walking to find its rhythm. Write it down, capturing both the words and rhythm patterns.

My children, I clothe your land, you see that Wampum before me, the body of my words, in this spirit of my words shall remain, it shall never be removed, this will be our Mat the eastern Corner of which I myself will occupy, the Indians being my adopted children their life shall never sink in poverty.

My children, see, this is my Canoe floating on the other side of the Great Waters, it shall never be exhausted but always full of the necessaries of life for you my Children as long as the world shall last.

Should it happen anytime after this that you find the strength of your life reduced, your Indian Tribes must take hold of the Vessel and pull, it shall be all in your power to pull towards you this my Canoe, and where you have brought it over to this Land on which you stand, I will open my hand as it were, and you will find yourselves supplied with plenty.