The Toronto Purchase Confirmation, 1805

The British decide that the best way to acquire a legally valid deed to the lands at York and to determine the nebulous boundaries of the Toronto Purchase (without drawing attention to the fact that they are doing so) is to negotiate a new cession of land along the north shore of Lake Ontario immediately to the west (what will become the City of Mississauga). The British make some initial approaches to the Mississaugas of the Credit in this regard.

But the Mississauga realize that their trust in the British has been misplaced. They are determined to receive better compensation should their impoverished circumstances force them to sell any more land. Before his death, Wabakinine had asked Mohawk War Chief Joseph Brant to act as an agent for the Mississauga in future land negotiations. Brant was a key British ally during the American War of Independence and although not a Hereditary Chief, he is a major power broker with the British and has sold some Haudenosaunee land on the Haldimand Tract at market prices (well above what the Crown would offer) in an attempt to set up independent funding for the Six Nations as they rebuild.

Colonial officials are alarmed to hear of a renewed and reinvigorated alliance between the Mississauga and the Haudenosaunee.

In 1805, conditions are finally ripe for the British to confirm the 1787 Toronto Purchase, finalize its boundaries, and acquire the lands to the west. They call the Mississauga to a three-day Council at the Credit River. The British have succeeded in sidelining Joseph Brant. The Mississaugas of the Credit will negotiate without him.

The Mississauga’s hunting- and fishing-based economy is collapsing because of settler encroachment. Alcohol has taken a massive toll, and measles and smallpox epidemics in the 1790s have killed 30 percent of the community: the population declined from over 500 in the late 1780s to 350 in 1798 and continues to fall. The generation of leaders who negotiated the Toronto Purchase has died, and with them, much of the memory of what was agreed to in 1787. As Chief Quinepenon explains at the 1805 Council, when the Mississauga are asked what boundaries their leaders agreed to,

All the Chiefs who sold the Land you speak of are dead and gone. I now speak for all the Chiefs of the Mississaugues; We cannot absolutely tell what our old people did before us, except by what we see on the plan now produced & what we remember ourselves and have been told.

At the 1805 Council, Chief Quinepenon makes it clear that while their knowledge of the agreed-upon boundaries is lost, the Mississauga clearly remember British promises made at the time of the Toronto Purchase, promises that have not been kept:

I hope you will open your ears and attend to what we have to say. When you first came up to purchase the lands at Toronto, Sir John Johnson told us the king wanted some land for his people to settle on, and they would be of great use to us. We gave them lands without hesitation, since we were told we would never live in poverty...

Father, we have not found this to be so. When we camp on the shore, they drive us off and shoot our dogs, and never give us any assistance, as was promised to our old chiefs. We want to know why we were served in this manner. The farmers threaten to shoot us, in the same manner, when we go on their land although we were promised to encamp and fish as we pleased.

In the negotiations, the Mississauga do their utmost to retain their fisheries, which are crucial for their sustenance and have become a means of participating in the emerging market economy. Chief Quinepenon tells William Claus, government negotiator and head of the Indian Department in Upper Canada, that in previous negotiations, the Chiefs “particularly reserved the fishery of the River to our Nation.” He reminds him that Colonel Butler had said, “We do not want the water, we want the land.”

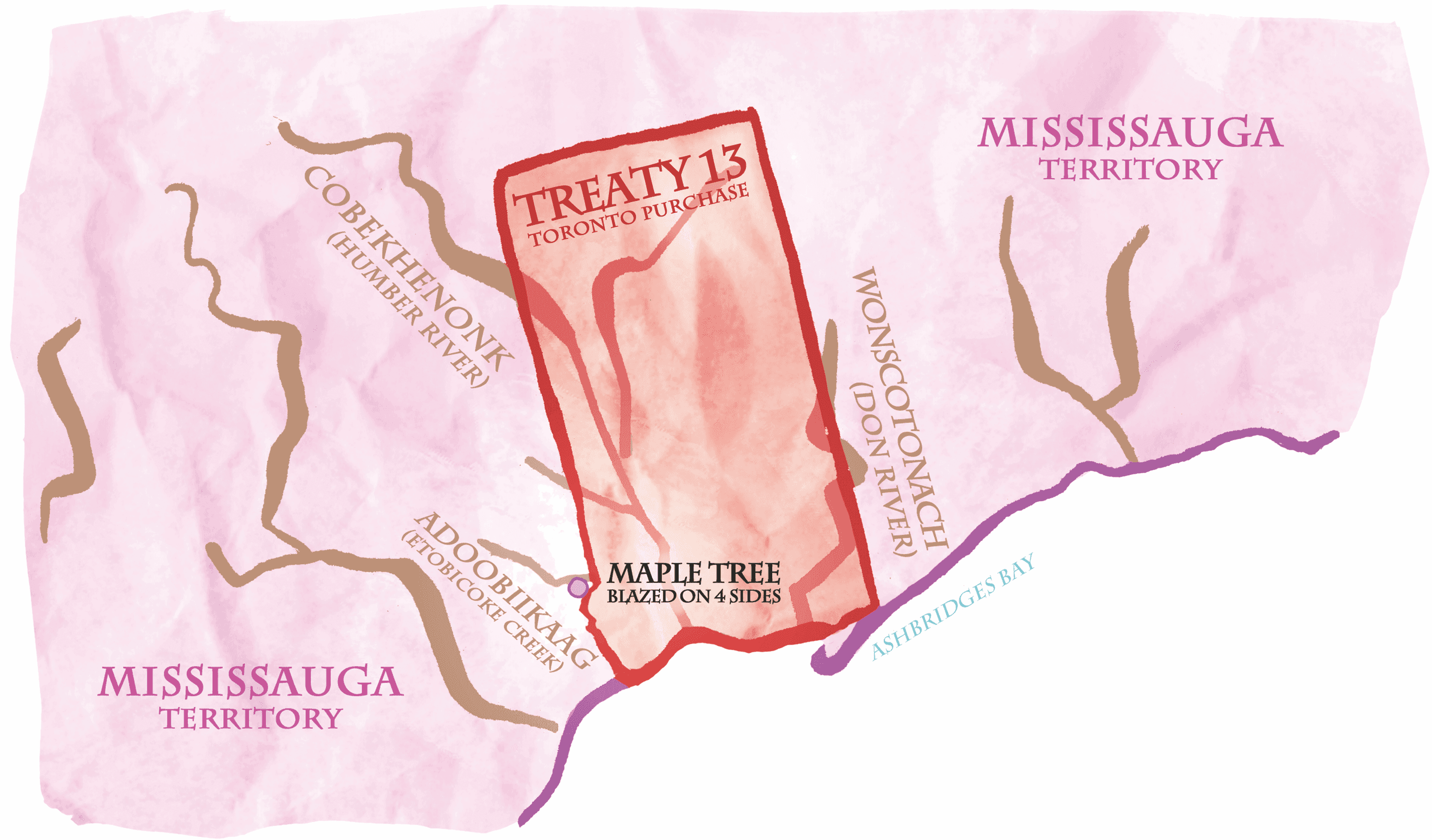

The British have come to Council with two maps in hand: one with the western boundary of the Toronto Purchase at the Humber River, the other roughly nine kilometres to the west at Etobicoke Creek. After it becomes clear the Mississauga have no firm memory of the boundary agreed to in 1787 and 1788, the British produce only the larger of the two maps, which also significantly extends the northern boundary of the Toronto Purchase to Newmarket.

Not knowing what their ancestors agreed to, the Mississauga confirm these boundaries, and the British acquire title to the lands between Etobicoke Creek and Ashbridges Bay in what becomes known as Treaty 13. The new boundaries greatly increase the amount of land ceded, without compensation. One year later, the surveyor general of Upper Canada will be dismissed, in part, it is claimed, because

he had shewn the Council their erroneous proceedings in a purchase of land from the Messessagua Indians, by necessarily shewing, in his official correspondence with them, how a false map had been procured, and the tribe thereby defrauded of seventeen thousand acres.

Is the Toronto Purchase a Treaty?

The nature of the agreements reached at the Councils between the Mississauga and the British in 1787 and 1805 remain contested. The federal government refers to the 1805 Toronto Purchase confirmation as Treaty 13 and the Head of the Lake Purchase as Treaty 14, but its official stance is that these agreements are land cessions. Take a minute to review what you’ve learned about treaty making within Indigenous legal traditions. Remember the promises made at Niagara. Do these Councils in 1787 and 1805 meet your understanding of treaty? What expectations would the Mississauga have had going forward?